.

. Goth chic

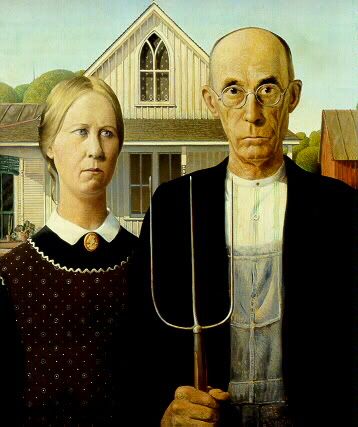

'American Gothic' has become a cultural icon. But why? And what is it really about?

By David Mehegan, Globe Staff | May 21, 2005

CAMBRIDGE -- It's the most familiar American painting, even more than Emanuel Leuztze's ''Washington Crossing the Delaware" or Gilbert Stuart's portrait of George Washington. It's instantly recognizable.

This year, Grant Wood's ''American Gothic" turns 75, and in his forthcoming book of the same name, Harvard historian Steven Biel tells its history and raises questions so simple that no one seems to have asked them before: What does this literal icon mean to America, and why is it the most parodied image since the Mona Lisa?

There are no simple answers, because the image has been interpreted in various ways by various people -- with anger, celebration, satire, even horror -- for 75 years. ''It is randomly adapted to almost anything now," said Biel, director of Harvard's program in history and literature, ''but if you look at it and try to get beyond the blandness that comes from having seen it so many times, it can be unsettling."

Biel's 1996 book, ''Down With the Old Canoe," was a similar treatment -- in that case of the various cultural understandings of the Titanic disaster. ''I seem to be attracted to things that have been flattened, reduced to cliché, over time," he said, ''and to recovering some of the richness of their meaning."

In advertisements for corn flakes, Saks Fifth Avenue, Paul Newman's organic produce, and even colleges, in political cartoons or television promotions (Paris Hilton's ''The Simple Life"), we continually see versions of the famous image of a woman and dour man holding a pitchfork, in front of a house with a Gothic window. Many of us, as a joke, have struck that pose for a camera, holding a rake, a broom, or a snow shovel. But what is the joke? That we consider ourselves heartlanders, or just the opposite? Or are we poking fun at the idea of a heartland? Or are we merely imitating a famous painting?

The story begins with a mystery. No one knows what Grant Wood, an Iowa painter with European training, was thinking in 1930 when he put together his sister, Nan Wood Graham, his Cedar Rapids dentist, Byron H. McKeeby, and a lonely little house in Eldon, Iowa. (Built in 1881, the house is owned by the state historical society.) Each element was modeled separately (Graham and McKeeby never stood in front of the house), then combined in Wood's mind and painting.

In later years, when the work was famous, Wood gave different explanations. It was merely a composition of forms, such as ''Whistler's Mother." The couple were a married farm family. Or they were father and daughter. Later still, he said that the man was a local banker or a businessman who liked to dress up in farmer duds at home. They were ''basically solid and good people," or they were ''prim" and ''self-righteous." But there is no record of his thinking before or during the painting's creation.

Its fame was a fluke. Wood entered it in the Art Institute of Chicago's annual painting contest, where it was dismissed as cloying. But a museum trustee implored the judges to reconsider. They did and gave it the third-place bronze medal, with a $300 prize. It became part of the museum's collection, where it remains. But fame rushed in with a reproduction in the Chicago Evening Post in October 1930, followed by appearances in rotogravure sections nationwide, including in Boston, New York, and eventually Cedar Rapids.

When Iowa farmers saw the painting, they were outraged, seeing it as another lampoon of small-town America, the sort of sneering at the ''booboisie" famously practiced by H.L. Mencken. Many critics, including an admiring Gertrude Stein, also assumed it was a satire. But Wood, stung by his neighbors' anger, called himself ''a loyal Iowan" who would never make fun of his state's people.

As times changed, so did understandings of the painting. In the Depression, some critics admired it as a celebration of authentic values, akin to the works funded by the Federal Arts Project. During World War II, some saw the farmer and his wife or daughter as symbols of triumphal strength. ''The Germans may today slay a thousand Danes," an Illinois pamphleteer wrote in 1944, ''but the man with the pitchfork knows that . . . he will have hay to pitch when the cows come home."

In the 1960s and since, critics have offered various understandings of ''American Gothic." One pointed out that ''gothic" also means horrifying, that dark and shameful deeds might lie behind the subjects' faces and veiled window. Robert Hughes wrote that Wood was obviously a deeply closeted homosexual, while Hilton Kramer attacked the work as kitsch that has no place in the canon of great 20th-century painting. John Seery saw ''Oedipal, generational, incestual" themes.

The image appeared in Meredith Willson's ''The Music Man," but the age of parody really got going in the late 1960s, when Nan Wood Graham (Grant had died in 1942) sued Johnny Carson and Playboy magazine for defamation. Carson had held up an image showing the man in bathing trunks and the woman in a bikini, while Playboy had showed her, of course, bare-breasted. Graham settled out of court but lost a similar 1988 suit against Hustler magazine. She died in 1990, and by then the flood of parodies was unstoppable.

''American Gothic" is fixed in the nation's collective brain, but perhaps mainly as parody. As an experiment, Biel showed ''American Gothic" to 59 Harvard sophomores and asked them to name the title and painter. Most of them recognized it, but only 31 knew the title, and only five could name the painter.

Uses of the image often stretch far beyond the original scene. ''There was a billboard I used to pass every day on Massachusetts Avenue in North Cambridge," Biel said. ''It showed two college kids advertising Quincy College in the 'American Gothic' pose. Maybe somebody can tell me what that has to do with Quincy College. There are parodies that use it in thoughtful ways, but it also tends to get used in an automatic, 'Oh well, everybody will recognize this' fashion." (A spokeswoman for Quincy College said the billboard promoted the fine arts department.)

''American Gothic" may work so well as parody because it's a kind of broad template. It shows middle-age, middle-class white people in the Midwest, apparently a family, before their middling house (neither imposing nor a hovel), an odd splice of agrarian and suburban elements, half home and half church. It may be that ''American Gothic" is the archetypal theme that we crave to vary. Possibly the earliest variation was Gordon Parks's 1942 photograph of Ella Watson, an African-American charwoman in Washington, holding a broom in front of an American flag.

Growing up in suburban Cleveland, Biel, 44, says he was immersed in television and popular culture, and is clearly sensitive to cultural imagery. His book, which will be published June 6, has authoritative analyses of ''American Gothic" in the 1960s sitcoms ''Beverly Hillbillies" and ''Green Acres." In addition to a large framed print of ''American Gothic," Biel's Harvard office is full of parody items, including a flip-book in which the painting gradually morphs into Edvard Munch's ''The Scream." He turns on his laptop computer to show the 1963 Country Corn Flakes ad, in which the painting's familiar duo sings, amid clucking chickens, ''It won't wilt/ when you pour on milk!"

Like ''The Scream," ''American Gothic" could not work as parody if the original did not have power of its own. Biel is not an art critic, and he hesitated to comment on the painting, apart from the myriad understandings others have had. But when pressed to do so, he gazed up at it over his desk and mused, ''It's haunting -- creepy in a lot of ways. Look at those faces. They're disturbing. Why isn't she looking at us? He is -- why isn't she? What does he want, peering into our souls? He is holding a pitchfork, but there's no dirt on it. Is he posing with it because this is Sunday afternoon and this is one of the tools of his trade? Or is there something -- more sinister?"

David Mehegan can be reached at mehegan@globe.com.

The Boston Globe

No comments:

Post a Comment